I’ve mostly used a coarse-ground Rye Flour as my starter for sourdough baking. I recently picked up some fine-ground rye (Roggenmehl 1370) which I noticed behaved a bit differently.

This got me curious, so I pulled out some strong white bread flour and some stoneground strong wholemeal flour to do a three-way comparison of these and maybe learn something about starter activity.

Ingredients

SWBF: Bob’s Red Mill Unbleached Enriched Artisan Bread Flour, protein at 13.9% (100g)

Wholemeal: Waitrose Duchy Organic Stoneground Strong Wholemeal Bread Flour, protein 14% (100g)

Rye: Roggenmehl 1370 a medium ground rye (similar to KAF Rye), protein at 11% (100g)

Room Temp Water 300g

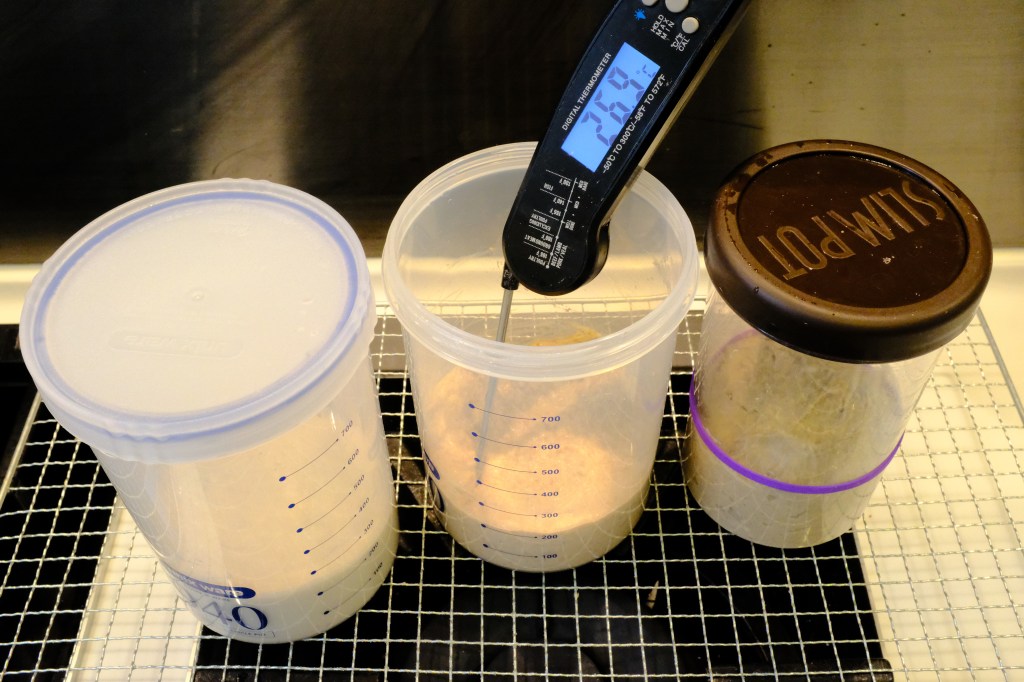

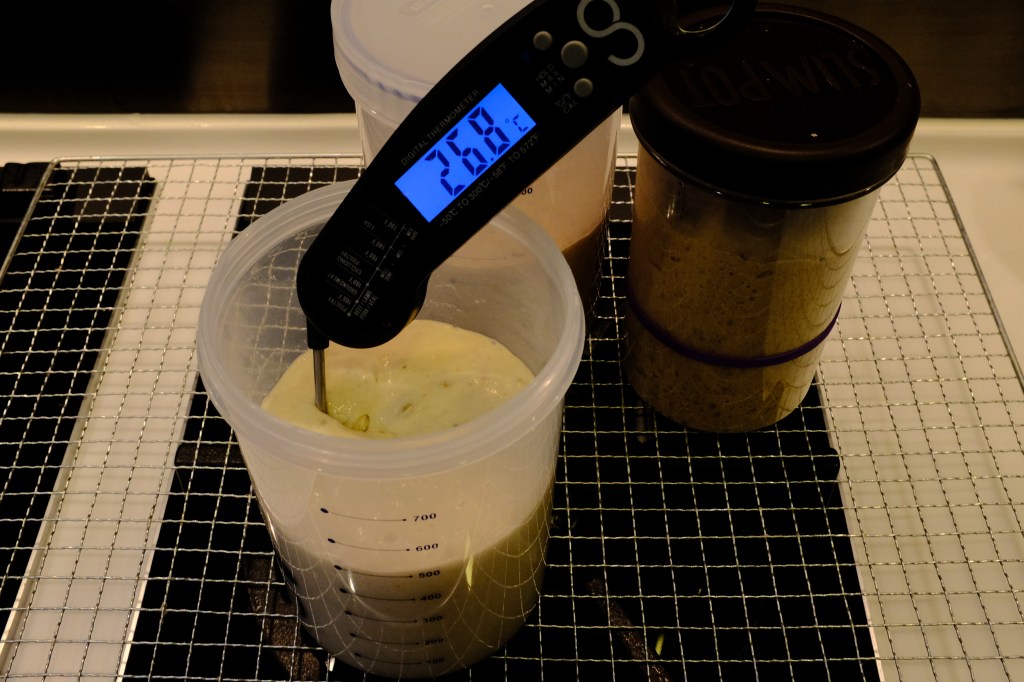

My kitchen was running at 26.8°C (about 80°F) on test day.

Method

I used my original rye flour starter and split it across three containers. Each had 50g of starter and then 100g each of flour and 100g water.

Due to water and flour temp, I ended up a little warmer once I had mixed the starter, flour and water.

From left to right: SWBF, Wholemeal and Rye. Time: About 1pm.

Sorry I didn’t have three identical containers. The original rye starter I used a rubber band to mark the starting level. The container on the right is slimmer than the other, so looks fuller from the beginning.

Each of them are running at around 250g:

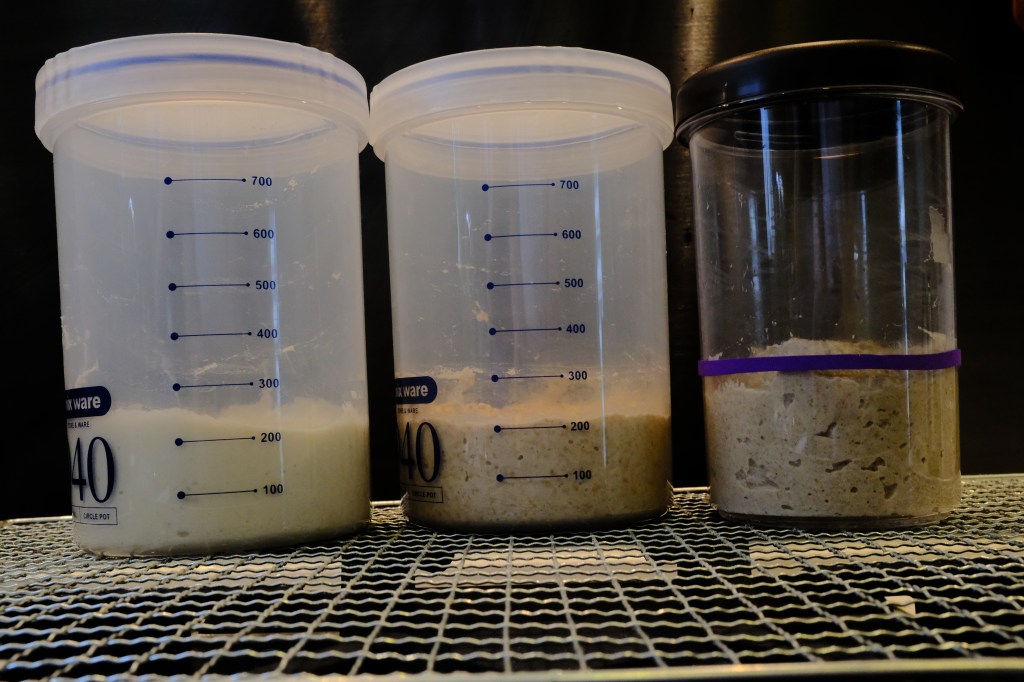

It lives!

Within two hours we can see some movement. This is approximately a 40% increase. The three samples are pretty even at this point.

Temperature was pretty consistent with room temp by this point.

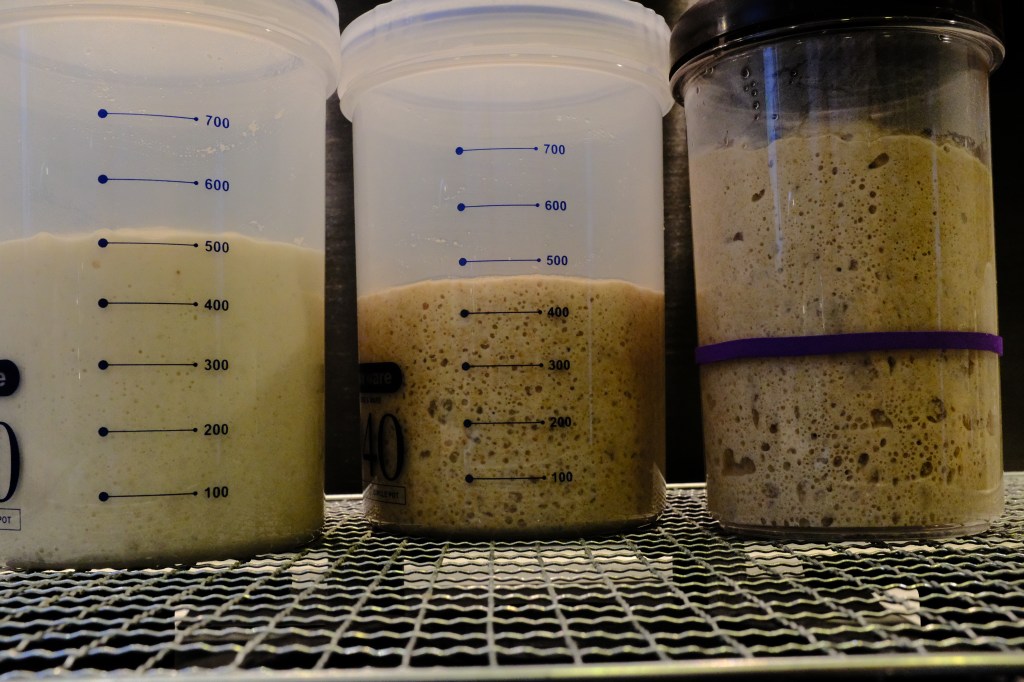

Fast forward another couple of hours.

After four and half hours we can see some real differences in the rise rate.

SWBF: around 250% increase

Wholemeal: approx 230% increase

Rye: approx 240% increase

By 7pm, six hours after beginning the experiment we can see some real differences.

SWBF: Around 270% increase

Wholemeal: Around 220% increase (started to collapse)

Rye: Around 200% increase (big collapse!)

The Collapse

So you can see the extent of the collapse at six hours for the rye here. It dropped from a maximum of nearly 300% increase. So the rye burnt brightly for a shorter time than the others, leading to a more spectacular collapse. If I wanted to use this in a bake then I’d need to use it after about four-and-a-half to five hours to hit it’s peak activity.

The wholemeal had also started to collapse at this point. Not as much as the rye, but still a small decrease in volume from around 250% at its peak down to 220% after six hours. I’d want to use this at around five hours from inception.

Going Strong

My last measurement was around 9.30pm.

The wholemeal and rye hadn’t changed much – their collapse was complete.

However, the SWBF was still going strong – after eight-and-a-half hours it was standing firm at a whopping 340% of the original mix. A little tap of the jar on the worktop and there was no collapse, so I guess it went strong in to the night. I wasn’t going as strong, so I went to bed.

I probably wouldn’t want to wait any longer if I wanted to use the SWBF mix in a bake.

Aftermath

The following morning, even the SWBF mix was spent. But as I was disposing of the experiments I noticed something quite obvious – the SWBF mix clearly had strong gluten development. The collapse wasn’t as noticeable, as the gluten strands kind of held the shape better. The starter was very stringy. Not surprising at 13.9% protein, this is a strong flour after all.

The small reduction in the volume of the wholemeal shows that it too was held together with gluten, but not as much as the SWBF. Dough was only slightly stringy. At 14% protein I expected more apparent gluten but I guess the stoneground nature works against it.

However the rye was nothing more than stodge. No gluten strands at all the following morning. At 11% protein I’m not surprised.

Thoughts & Conclusions

The wholemeal and rye hit their peak relatively quicker than the SWBF. They were ready to bake with in five hours, and could have been used even earlier I think, maybe four-and-a-half hours. I figure the greater nutrient content leads to faster generation of gas, but is not conducive to strong gluten development in those flours.

I didn’t get an accurate read on the peak of the SWBF but it was looking strong nearly nine hours and 350% increase later. Clear more of a tortoise than a hare, but good to know that the window of opportunity was bigger than for the wholemeal or rye.

By that, I mean that the period of peak activity lasted longer than for the heavier flours, and could have been used anywhere between six and eight hours after mixing.

Overall, this not-very-scientific experiment certainly demonstrates that different flours develop at different rates – so when you recipe says “Let rise for six hours” or whatever, what they really mean is “let rise until peak activity is reached”. That is when you should be adding your starter to your bake. So if you like to autolyse, you need to start that earlier too (assuming you autolyse only flour and water).

Following that line of thinking, the flours you use will have a massively different show of force during the bulk ferment and second rise also. From this I would expect recipes with heavier flours to bulk and rise in less time than the purely white flour recipes, making over-proofing a risk with these flours if you’re following recipes for SWBF.

And I’d expect them to have lesser gluten development too. Which matches what we know about getting purely wholemeal or rye loaves to rise properly. So if your wholemeal sourdoughs are not rising enough in the oven, maybe you’re over-proofing and not leaving enough oompf in the flour for a good oven spring.

The other thing to consider is my kitchen temperature – at 26.8°C (about 80°F) that is considered quite a warm kitchen. Apparently most kitchens run about 21°C to 24°C (70°F to 75°F). So in your kitchen the same flours might take longer, or shorter, times to hit peak activity.

It all boils down to this: learn your ingredients. It is most likely that conditions in your kitchen differ from the recipe author’s. So learn how starters behave with different flours in the temperature of your workspace. Experiment to find that peak activity for your bakes and work your routine around those times for consistently good loaves.

A baker in the arctic circle is not going to have the same experience as a baker in the tropics. Kind of obvious, isn’t it?